Coping with the Blitz

Growing up in war-time WGC

By Nicodemia

The War broke out when I was rising 5. We moved to Welwyn Garden City- Dad took over the Optical practice of Mr. Musson, who apparently had an invalid wife, and wished to remove her further away from the Home Counties. Our first house was in Coneydale, right on the edge of WGC. In front was a small green – typical of WGC, which had what seemed to me huge oak trees on it, and at the back were fields and woods.

Sherrardswood

Immediately behind the house was a field, and at the top of that, a small wood, part of Sherrardswood, where there was a huge rabbit warren. We could see the rabbits from the bedroom windows, but I imagine they caused havoc among the vegetable gardens! To the right of the field was a bigger field, which went over the hill and down the other side. We called this field the “Observer field” as at the top was a concrete bunker-thing, where members of the Royal Observer Corps spent their nights and days watching for enemy aircraft. We used to go mushrooming in that field in the mornings. We used to collect quite a lot, but there was always someone there before us, however early we set out! At one time in the War we had Austrian refugees – who must have been Jewish. I don’t think they stayed long, and after that we had Pam Secker, who was evacuated from Hastings. She was a lovely girl, and taught me to roller skate. She went to Handside School – I suppose she walked, quite a way – in her box-pleated tunic, which I envied! She kept in touch for a while after the war, eventually she married and went to South Africa.

Bombing in Coneydale

In October 1940 we were bombed out of Coneydale. At the time Aunt Connie was with us, and also Granny and Grandad Norris, who had come up from Herne Bay thinking it was a safe place! I suppose the bombs were dropped from an aircraft ‘shedding its load’ having got off course from London, which was only 20 miles to the south. On the other hand, we always thought that the Viaduct, which carried the main railway line from Kings Cross to the North and North East was a prime target. Who knows who was right? The night of the bombing Vivie and I were under the stairs – quite a sensible place, as the interior walls would have been strong there. Aunt Connie was on a camp bed in the hall. Granny and Grandad Norris were asleep somewhere and Mum and Dad pottering about. I don’t remember the actual bomb, but I do remember being taken, in the dark, to a house just a big further along the road, and sleeping there. The next door house had also been bombed, the bomb going right through the woman’s bed, only she had just got up to make a cup of tea! Because next door was an oil bomb, and because there were boilers, etc. the Fire Service, or was it the Home Guard, sat all night, hoses at the ready, on the green outside the houses. In the morning they found they had been sitting over an unexploded bomb! It was later detonated, or made safe, or something. We all had to leave our houses. In the morning an unidentified older girl, who took me to school and said ‘This little girl has been bombed out’. I was wearing borrowed clothes, and joy of joys WHITE sandals – never allowed in our house – properly-fitted-Clarke’s-sandals or nothing there! For the rest of the week we slept on the floor at the house of a Mrs. Douglas, somewhere near the woods. She had a really naughty son, called Charlie Douglas, who was the bane of every teacher’s life. I seem to recall she was a bit of a ‘hippie’ before her time, vegetarian, sandals, and Mr. Douglas was incredibly clever, a scientist I think and frighteningly intellectual. There were quite a few like that in WGC. After a week or so we moved to 31 Digswell Road, rented to us by the man who owned the Opticians, Mr. Musson. It was decorated in truly revolting shades of sort of stippled oil paint. The hall was brown, yellow ochre, an evil green, and the front room was a bit better, being blue, pink, pale green etc. I think the dining room was also awful browns and greens, or maybe creams and things.

Friends in Coneydale

We had several friends in Coneydale and around. My special friend was called Janet Power, but there were also a family of boys up the road (the Orrs) and Vivie had a friend Rita. We would roam the nearby fields and woods with a lot of freedom, and used to collect the tin foil, called ‘window’ dropped to confuse the radar. I also remember finding a big crater somewhere, and looking at that. I told Mum later it was quite safe, the notice only said ‘unexploded bomb’!! In order to supplement the rations we collected mushrooms and blackberries. The last were from the Quarry at the back of Coneydale, further up, and had really big luscious ones.

Food rationing

At least one year we collected rosehips and took them down to the Council Offices to make Rose Hip Syrup. I have a vague idea we got paid 3d a pound, which would be about 1p!! Food was always difficult in the war. It was rationed, of course, but there was a black market. Dollimore’s came every week in a big van, with fruit and vegetables, also rabbits, shot on their farm (mind your teeth on the shot!), and black market feed for our chickens. They were up in the far right hand corner of the garden, in a lovely big run, and supplied us with plenty of eggs We used to preserve the eggs in horrid slimy waterglass, but were glad of them later. Mum did a lot of preserving of fruit, in big Kilner jars – huge ones for plums, and smaller ones for blackberries, black currants, etc. We grew quite a lot of vegetables, and also had gooseberries and blackcurrants, though I’m not too sure if we had those in the war. Rations, especially as the war dragged on, were very small. Many ships were being sunk in the Atlantic by German U-boats and we were all urged to “Dig for Victory” by growing vegetables. We grew runner beans, broccoli, cabbages, spinach, carrots, and had various fruit bushes. Meat was sold by price — each adult person was allowed 6d (old pence) worth of meat a week, so if you bought cheap stewing meat you got more! (On the other hand you got more bone!) We were also allowed 1d worth of corned beef. These amounts were very, very small. The bacon ration was equally minute. Adults had 2 oz tea, 1 oz cheese, a quarter pound of sugar, an ounce of butter and 2 oz margarine (or other fats) and 1 egg. That lot was for a week. There was also a “points” system. Each person was allocated so many “points” (actually coupons in your ration book) to spend as they wished, providing the stuff was available, on things like jam, tinned (canned) fruit, fish, meat etc. You could also use some of these points for sugar if you made your own jam, which my mother did, in very large quantities! We kept hens up the end of our garden, so didn’t get our egg ration, in return we got some sort of chicken meal, which we mixed with ancient potatoes boiled to a mush, and which the hens went mad over. They also got greenstuff from the garden. Growing your own vegetables was OK if you had a garden, but thousands of people didn’t, and they had to manage as best they could. Surprisingly, we were all healthy, and I’ve recently read that children then were healthier than children now. We took a lot of exercise. We had to. No cars, few buses, we walked everywhere. All our groceries came from Welwyn Stores, known as ‘The Stores’. When rationing was in force, you had to register with a grocer, and butcher, and stay with them, unless you moved. There were only two food stores in the centre of WGC – The Stores and The Co-op. The Co-op was considered to be common, but on the odd occasion I did go there, I loved the little jars that contained the money and went whizzing along the wires to the cashier, and then back again with the change. The rations were very small, how everyone managed I don’t know. Every morning on the Wireless there was a food programme, – was it called Food Front? – with helpful hints and recipes for making a very small amount of anything go a very long way. If you didn’t have chickens, then eggs were unobtainable, and you used dried egg. It was fairly revolting as an omelette or scrambled egg, but could be quite palatable as a sort of fried fritter, or done as ‘eggy bread’, and was fairly successful in cakes. Trouble with cakes was there was no fat, so they all tended to be very dry. No dried fruit, of course. Sweets were unknown, though I vaguely remember the occasional chocolate, perhaps a chocolate egg for Easter?

School life

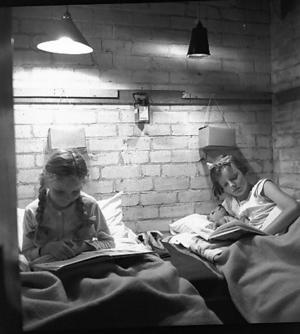

At school we had shelters up beyond the tennis courts. They were sort of Nissen hut shaped, partly underground, and the corrugated iron roof was well sandbagged. Inside they had long benches along the sides to sit on. They smelt damp and airless and were fairly frightening, though we did go in them several times. Air raids were fairly frequent, as bombers used to come north from London. The siren was an awful, wailing sound, which struck terror in our hearts at first, though later we got quite blasé about it. The All Clear was a continuous, cheerful sound. During the Blitz of London we could see the glow of the fires from the upstairs front windows. We were quite high at WGC, and there wasn’t so much building in the way as there is now. The fires looked terrifying. What were really frightening in the war were the Doodlebugs. By the time they reached us they had overshot their target, were running out of whatever propelled them and were sure to come down. I think a couple of houses in WGC were hit, and there were some deaths, but mainly they fell in the fields. But it wasn’t as bad as South London, where it was known as Doodlebug Alley, and the devastation was dreadful. Vivie had a really acute ear for them – if she said a Doodlebug was coming, it was coming, even if no one else could hear it! We had a splendid shelter at Digswell Road in what was the Coal cellar (Known as the Coles in the Coal Hole!) It was sandwiched between the garage and the house, and had been strengthened on the roof, the windows had big iron shutters, and the garage side was sandbagged right up to roof level. Outside, in the garden was the ‘blast wall’ a thick brick wall built 2 or 3 feet away from the house, designed to minimise the effect of blast from a bomb. In the shelter we had two bunks, mostly occupied by Vivie and me, though if the danger was acute, then Mum and Dad would come in too, and Vive and I would share a bunk. No sleeping bags then, we used old blankets, and the dark grey ones issued us for the evacuees we no longer had. It was still cold though. We did have electric light, though of course, kept several torches at the ready. Towards the end of the war we would see waves of bombers going over to Germany in the evening, night bombers I suppose. Then in the morning we would see them coming back, tragically so many fewer, some of them obviously limping along.

The wireless

The Wireless was our lifeline. No TV, of course. I don’t think we had any sense of not being told the truth, though I am sure now (1996) that we were fed a lot of propaganda, and mis-truth. A named announcer always announced the news – so that we could tell if it wasn’t really the BBC. You got to know the voices of the readers – John Snagge, Alvar Liddell, Bruce Belfrage. At lunch time there was ‘Workers Playtime’ – a light entertainment show from a factory ‘somewhere in the Midlands, or North or wherever. You never knew where. There was always a raucous noise from the audience – I always imagined them sitting at their canteen tables, banging their cutlery. I may well have been right! Children’s House was at tea-time, with Uncle Mac, and all the other Uncles and Aunts. We loved it. It all seems so innocent now. I remember Toy Town, with Larry the Lamb.

Down by the Campus was what I always understood to be a Prisoner of War Camp – though I have my doubts as to the accuracy of that! It seemed to house Italian prisoners, and wasn’t really very big. At the end of the war they all disappeared.

Peace breaks out

When VE (Victory in Europe) Day was declared everyone went mad! There were fireworks and a bonfire in the town, which we were taken to see, though we didn’t have a street party like so many did. Our road was a bit too “up market” for that, and my parents too “snobby”. It was some months later that victory was declared over Japan, and then there were the horrors revealed of the Japanese POW camps. I don’t think I found out an awful lot about those until I went to the Grammar (High) School, and we had a history master who had been a POW under the Japanese.

Rationing for basic foods lasted for several years after the war, and I remember that butter and margarine did not finally come off the ration until after 1952 when I went up to University, clutching my ration book.

Unfortunately, we do not know the name of this contributor, apart from her surname Cole. If you are this lady, please let us know, or, indeed if you knew her or have similar memories of wartime in WGC, please share them with us.

We acknowledge the thanks of the BBC People’s War website for permission to use this piece Nicodemia/WW2Peoples War

Add your comment about this page

Reading between the lines it seems very possible that this lady’s father was John Cole the optician of Howardsgate. She talks of her ‘snobby’ parents not having a street party. My memory of John Cole is that anyone less snobby it would be difficult to imagine. He prescribed my first pair of spectacles.

Interesting reading. Just before the bombing mentioned we too were bombed out of our Handside Lane house (No.63). I was sleeping “under the stairs” one October night when London was ablaze, and suddenly my Father and our large dog threw themselves on top of me. The front of the front of the house was destroyed. eventually the whole house was leveled, and rebuilt after the war. We were able to climb out of the rubble with only a few cuts from shattered glass. A good ending to the experience for us, although my mother was in hospital at the time, and the dog who helped save my life had to be put down because of lack of accommodation for us all.